On a vu que si une grosse étoile meurt, elle pourra donner naissance à un trou noir.

Un trou noir est un endroit dans l’espace où la gravité est tellement forte, que même la lumière ne peut pas en sortir. La gravité est si forte parce que la matière a été compressée dans un espace minuscule. Cela peut arriver lorsqu’une étoile meurt.

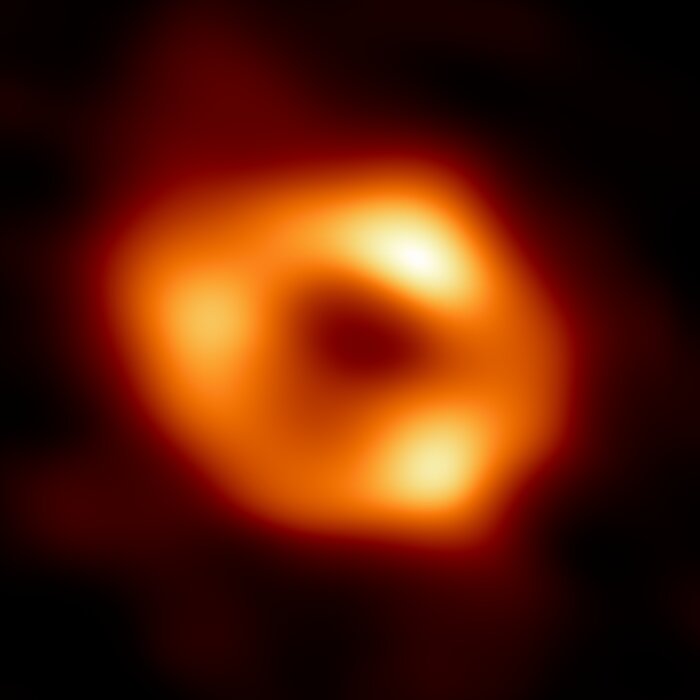

Parce qu’aucune lumière ne peut sortir, on ne peut pas voir les trous noirs. Ils sont invisibles. Les télescopes spatiaux dotés d’outils spéciaux peuvent aider à trouver des trous noirs. Ainsi on peut voir comment les étoiles qui sont très proches des trous noirs agissent différemment des autres étoiles.

Un soir, repérez vous dans le ciel et rechercher la constellation du sagittaire, au bout de la voie lactée. Regardez bien, c’est là que se trouve le trou noir de notre galaxie, regardez bien, on ne peut pas le voir…

Sur le site de l’Eso.org vous pourrez découvrir de superbes images prises par les télescopes et offertes au public ; c’est une invitation au rêve.

Un trou noir…

On en entend parler, on en a détecté… mais qu’est-ce que c’est ?

Encore une fois, Henry va nous l’expliquer