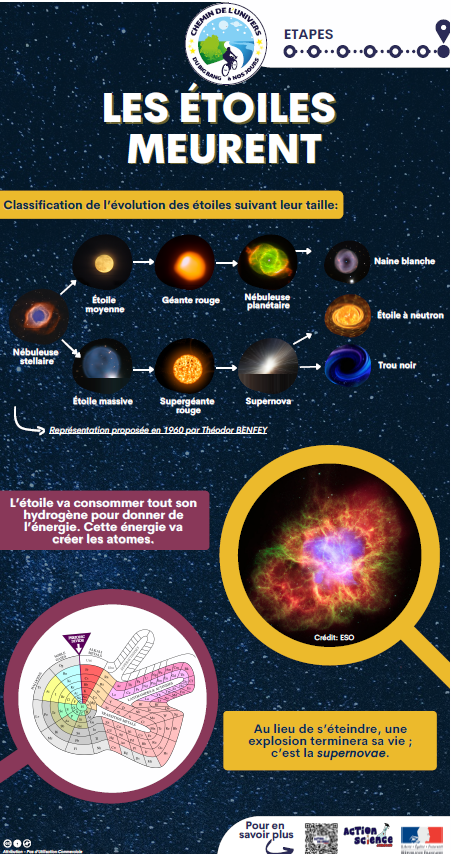

Il est possible de prédire la vie d’une étoile à partir de sa taille. Ainsi, 3 grandes catégories ont été identifiées :

1- les étoiles les plus petites vont se consumer régulièrement jusqu’à s’éteindre en s’effondrant

2- Notre Soleil est une étoile de taille moyenne, juste au milieu de sa vie. Il va continuer à se dilater pour devenir une géante rouge, puis s’effondrer pour finir en naine blanche ; ce sera un astre gros comme la terre mais avec la masse du soleil, mais sans activité.

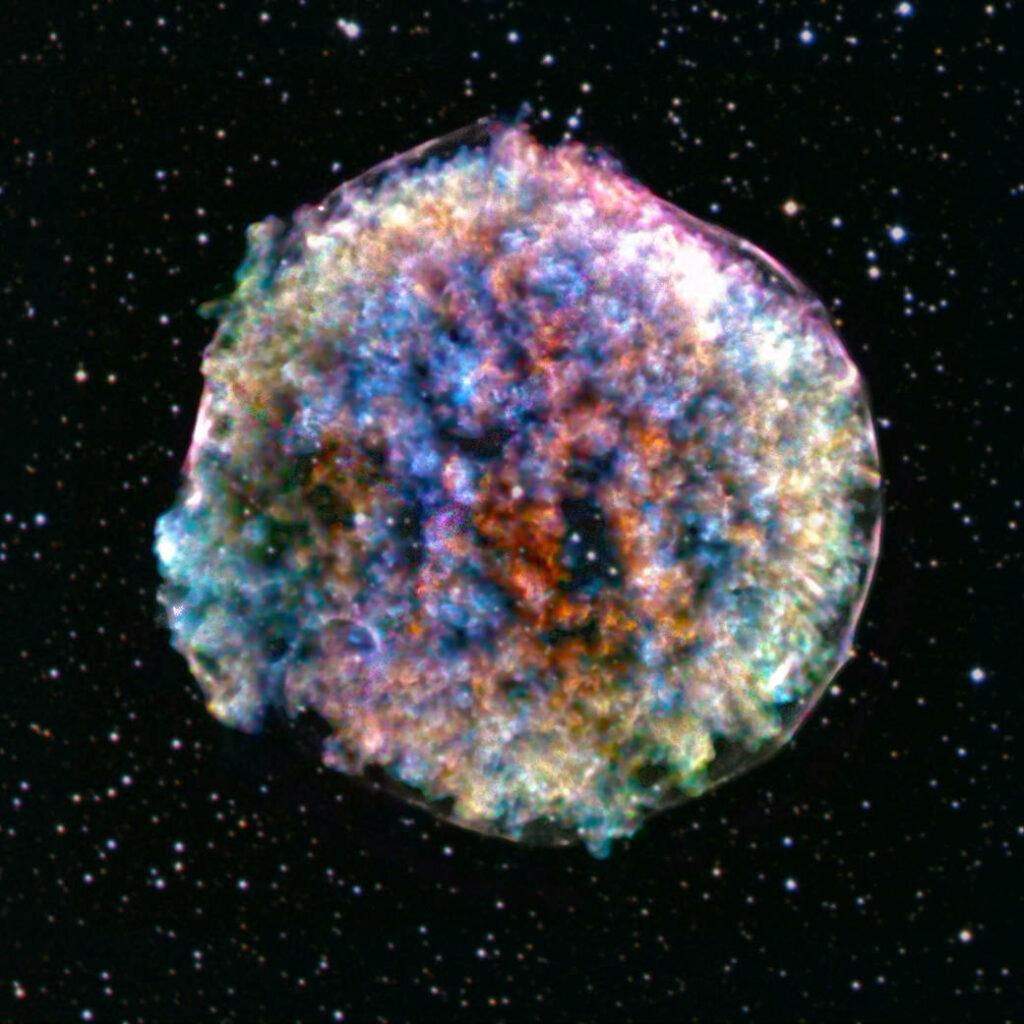

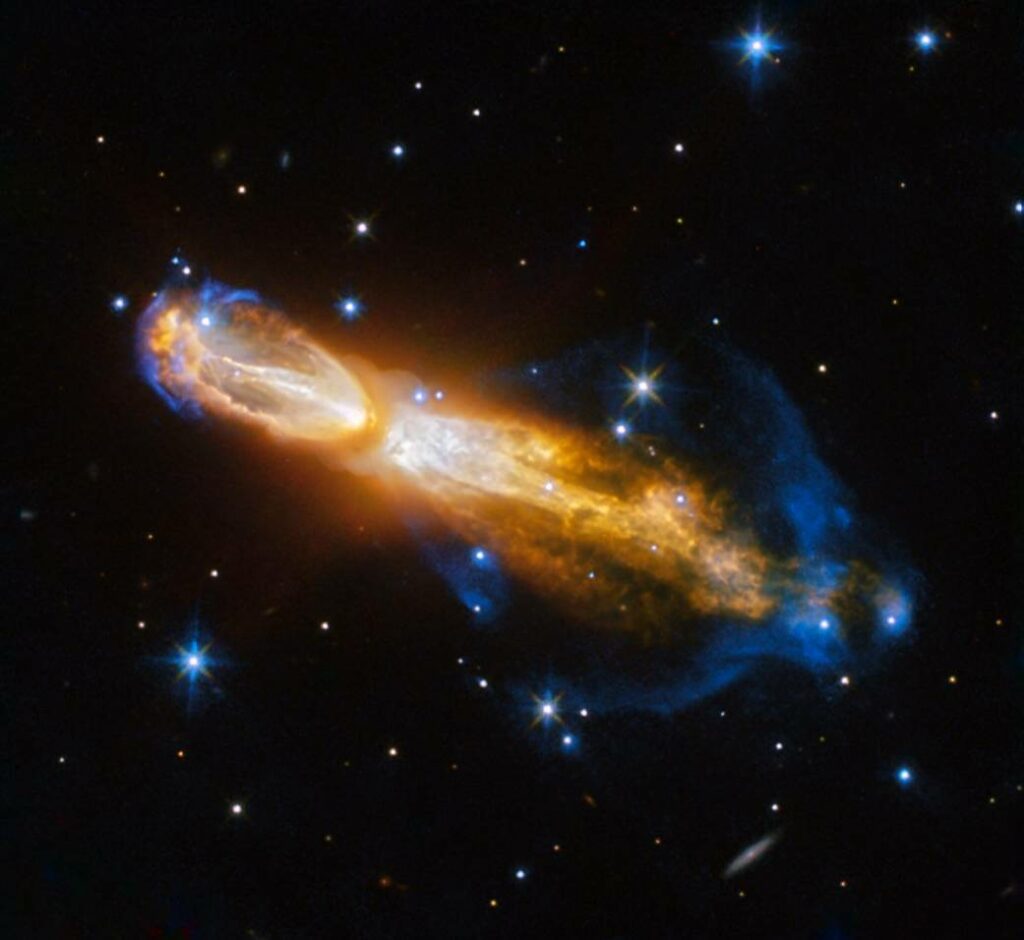

3- les plus grosses étoiles sont plus impressionnantes ; elles finiront en supernova, puis pourront évoluer en étoile à neutrons ou en trou noir

Ce n’est pas parce qu’une étoile est grosse qu’elle vivra plus longtemps, tout au contraire.

L’étoile se meurt. Elle a déjà fabriqué beaucoup d’éléments, et elle finira en apothéose.

L’énergie libéré lors de l’explosion d’une supernovæ est immense.

L’énergie de fusion de l’hydrogène n’est plus là pour inverser le sens de la force gravitationnelle, puisque le réservoir est épuisé.

La force gravitationnelle est à l’origine de l’explosion finale. C’est là que les autres éléments que nous connaissons sont synthétisés par fusion nucléaire.

Ça y est! Nous voyons enfin tous les éléments qui nous sont familiers sur notre Terre!

Si la masse de l’étoile est trop importante, alors il n’y aura pas de supernova … mais un trou noir…

Nous sommes des poussières d’étoiles

Parce ce que la matière qui forme notre chaire a été formée par l’étoile qui a donné naissance à notre système solaire

Mais nous avons aussi besoin de la poussière de supernova pour donner la diversité des atomes formant notre Terre !

Nous sommes des poussières de supernovæ.

Une étoile, ça peut mourir ?

Et oui, les étoiles naissent, grandissent, puis meurent

Continuons notre route avec Henry pour comprendre la vie des étoiles